Abstract

Pharmaceutical expenditures have been increasing much faster than spending on other medical services and have become burdensome for policy makers and stakeholders in the medical society worldwide. From 1997 to 2008, overall national spending on pharmaceuticals in Taiwan increased from 64.0 to 125.1 billion Taiwan dollars (NT$); and remained approximately 25% of total national health expenditure. As a consequence of that development, that additional expenditure must either be financed or it must in one way or another be constrained; both approaches will probably have to be adopted in parallel. Because either increasing public spending or increasing patient sharing may meet with different level of difficulties, cost control has attracted considerable public attentions.

This paper presents cost-containment strategies that have been adopted by the policy makers and health providers who are responsible for formulary management with the promise of cost saving; and discuss some other thoughts that might be attributable to cost saving and improve the value of pharmaceutical expenditure in the long-run.

Key Words: cost-containment strategy, pharmaceutical expenditure, restriction on drug utilization, pricing policy, health technology assessment (HTA)

Common Strategies for Controlling Pharmaceutical Expenditures

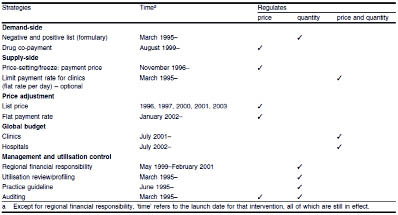

More than 30 specific cost control strategies have been published between mid-2002 and mid-2004 under three broad themes: utilization, pricing, and regulation.1 Although there is no formal information on the efficiency among various cost containment strategies, some of these initiatives hold a promise for cost-containment. In this section particular selected strategies are placed on those principles which have implemented in Taiwan since the inception of NHI program (Table 1)2.

Table 1. Cost containment strategies in Taiwan, 1996-2003 (with permission from Pharmacoeconomics)

The NHI program in Taiwan is mandatory and administered by the Bureau of National Health Insurance (BNHI), under the jurisdiction of the national government's Department of Health (DOH). The NHI's pharmacy benefits are comprehensive, including prescription, traditional Chinese medicine, and preventive medicine (e.g., immunizations). The descriptions for covered pharmaceuticals list in the“Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme for National Health Insurance: Chapter 2, The Principles on Drug Reimbursement Listing in National Health Insurance 2008”. As a single-payer entity, the BNHI operates considerable monopsony power over reimbursed fees, drug prices, and other "terms of engagement" with healthcare providers.

Utilization Strategies

There is a variety of strategies which tend to affect which and how many prescription drugs patients use. These approaches range from exclusion of specific drugs or drug classes from coverage (e.g., positive/negative list formulary), a direct limit on quantity, management on utilization (such as a prior authorization requirement, generic/therapeutic substitution, step therapy or first failed requirement and utilization review), to designated payment scheme (such as case payment) and to methods influencing how much the patients pay (such as cost sharing by patients).

Direct Limits

Insurance plan sponsors may choose to exclude certain drugs or classes of drugs from coverage. Often, these exclusions represent a design decision of what types of services plan sponsors want in their health plan. Thus, they may exclude weight loss products, birth control pills, or life-style drugs. In Taiwan, all new drugs are evaluated and get approved by the Bureau of Pharmaceutical Affairs (BPA) within the DOH. Inclusion and/or exclusion certain drugs or classes of drugs in the NHI coverage are decided by the BNHI. In 1996, BNHI established the Drug Benefit Committee (DBC) which is responsible to make three recommendations to the BNHI regarding new drug reimbursement: whether a new drug is listed or not, any restrictions on coverage, and a reimbursement price. If a product is approved by BNHI, it is added to the reimbursement list which allows for the formulary enrollment of the new drug at any healthcare facility in Taiwan.

The main purposes of utilization review (concurrent or prospective DUR) are to restrict filling a prescription based on factors such as duplication, interactions with other drugs, excessive dosage or duration, or diagnostic appropriateness. Concurrent DUR typically generates a flag for the pharmacist, who can override the flag either based on his or her own assessment or after consultation with the prescribing physician. A growth body of evidence indicating that concurrent DUR system can reduce drug costs through the avoidance in inappropriate drug use, overdoses, therapeutic and/or ingredient duplication and safety-related concerns.3 On the other hand, the retrospective utilization review is conducted sometime after the prescription as been filled. Generally, these programs determine patterns of drug utilization and costs and provide information in some form to payers, prescribers, and pharmacists with the goal of correcting problems. Medical treatment review in NHI program is retrospective and does not hold a measurable effect on reducing the frequency of drug problems, or on lowering spending or other health services. Results of these retrospective utilization reviews were focus on violations of NHI regulations and detection of fraudulent medical claims.4 Automatic concurrent DUR system should be one of the more efficient cost containment approaches, being increasingly a basic element of electronic claims processing. The implementation of IC card can overcome the challenges of retrieving medical information for patients who filled medication at different facilities or pharmacies.4 With respective to the quality of DUR criteria, Fulda et al. study recommended technical improvement on more validation of criteria through evidence-based studies, performance standards for pharmacists and payment to pharmacists for time spent identifying and addressing drug therapy problems. 5

Utilization management approach

Some utilization management strategies are mostly focus on substituting a different drug for that originally prescribed. For examples, step therapy or fail-first requirement is a program where payment for a drug is restricted unless certain other drug therapies have been tried first. Another example is therapeutic substitution or intervene, which encourages the substitution of original drug with lower-priced, therapeutic equivalent alternative and is commonly operated by pharmacists or pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in the U.S. It is difficult to decide how well the therapeutic substitution/intervene programs achieve their goal of reducing drug costs because there are limited data on cost savings attributable to these programs.1 Generic substitution is another type of drug interchange program used extensively worldwide. The potential for savings from increased use of generic drugs is substantial as generics cost 40% to 60% less than their branded equivalent drugs. Analyses for the use of generic substitutes during 1997 to 2000 in Medicaid and employer-based insurance programs, show optimal use of generic drugs could yield significant savings.6 To respond very rapid growth of pharmaceutical expenditure, aggressive actions for promoting generic substitution often through legislation process is part of government efforts to reduce drug costs in many countries in European area, and Asia countries such as Japan. But increasing attentions have been brought by some disputes over the therapeutic equivalence of generic substitutes for brand name drugs. The arising issues and concerns are discussed in the next part of this article.

One of most compelling methods influencing drugs utilization is the payment scheme of providers. The payment system of NHI program has been gradually transformed from fee for services (FFS) basis to prospective payments, such as case payment, global budget, flat reimbursement rate of payment, involve transferring spending responsibility to health providers and are a way to influence utilization by reducing drug use or shifting to a lower cost drug. The potential saving for each existing prospective payment strategies (case payment, global budget, and flat reimbursement rate of payment) in NHI program has not been clearly defined.2 Particularly the current structure of the global budget, which sets a cap on allowable increases in annual spending on the large hospital facility remains controversial effect on healthcare cost saving in the long-run.7 The problem is that, to keep total medical expense within the fixed budget, hospitals might limit the volumes or level of services, replacing high-quality drugs with lower-priced or more profitable substitutes and further increase the possibility of compromising the quality of care.7

The BNHI implements another prospective payment mechanism, Tw-DRGs (Taiwan Diagnosis-Related Groups) system and gradually being effective with 155 groups covering 17% inpatient expenditures. Under the system, each DRG is given a fixed level of reimbursement, which ensures that hospitals rationalize patient treatment and confine all related costs within that level.8 Although experiences with DRGs in the U.S. has been credited with the successful control of hospital expense,1 there were controversies in the process of DRGs development. The often cited concerns were DRG's categorization, severity of the case-mix, hospital's financial condition, and access to expensive care or medicines.1

Pricing and Regulatory Strategies

Pricing strategies aim at lowering the price paid for drugs rather than modifying the utilization of drugs. The pharmaceuticals market is for various reasons not fully comparable to the normal competitive market in which the individual buyer is to a large extent able ensure that the buyer gets value for money. In Taiwan, as a single-payer entity in nature, the BNHI is expected to intervene at many points distorts competitive market operation. Since the NHI inception, the BNHI has operated a series of drug reimbursement price adjustments since the NHI program introduced in 1996, through either international/inter-brands comparisons, market price and volume survey, or grouping.4 The latest (6th) price adjustment for reimbursed drugs, covering 7,600 items was conducted in October 2009 in combination with market price and volume survey and grouping to narrow the drug price gap and variation in prices among pharmaceutical products with the same active ingredient, same strength and same dosage form.

In the grouping (i.e., generic grouping or reference grouping) price policy, there are two main categories based on the quality of pharmaceutical products, original branded versus BA/BE (bioavailability/bioequivalence) generics, and other generic products without BA/BE studies. The guideline for price regulation process and imputation of the adjusted price in each item of BA/BE generic products is described in the“Guidelines of Price Adjustment for National Health Insurance Reimbursed Drugs”. In the guideline, the BNHI offers a great competitive advantage to the domestic generic manufacturers in facilitating market entry. As a single-payer in nature, the BNHI is used to set directly the price paid for off-patent, BA/BE generics as usually from domestic factories, equal or proportionally less than original branded product with identical ingredient, even though they do not have the astronomical R&D investments of the branded drug manufacturers to make up. The consequences of generic grouping strategy led to potential obstacles of innovation, concerns with the quality assurance for generic substitutes, and intrinsic efficacy of medication therapy are doubted.

In the recognition of the problems, the BNHI recently made advances relates to quality of local generic products. To win the BNHI reimbursed price equivalent with the branded drug, the generic manufacturer has to fulfill with the regulatory requirements, including approved BA/BE studies, drug master file (DMF) for substance, compliance of PIC/S GMP guidelines (The Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention and Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme for Good Manufacturing Practice), U.S. FDA and/ or EMEA (Food and Drug Administration/European Medicines Agency) approved ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application), drug labeling and patient-centered approach for drug package.9 Such reforms could be implemented in stages leading to the improvements of local generics and endeavors in making generics. Nevertheless, the controversy is supported by reports of the lack of therapeutic equivalence between some generic products and brand-name drugs in critical therapeutic categories, including warfarin10 and drugs for cardiovascular disease,11 psychiatric and neurology diseases.12 With the increase in availability of generic drugs in the recent and near future, the results of bioavailability and bioequivalence (BA/BE) for generic products have received increasing attentions. More importantly, although price regulation plays a substantial role in the Taiwan's NHI program, price reduction does not stop the increasing growth of drug spending. Possible causes include the volume expansion of existing drugs and expansion and substitution of the new drugs for existing drugs.

Other Strategies Approaching Quality Improvement

The BNHI continues to face increasing financial pressure, it is likely that there will be further restrictions and cost containment strategies on the use of pharmaceuticals in the future. The challenges widen with as the growth of demand on better quality of healthcare and aging population. The true art of cost control on pharmaceutical spending is clearly to ensure that drugs continue to benefit society, while eliminating every form of waste of public funds. The BNHI influence should not limited to the financing of health care, but extends also to the organization, standards and delivery of health care in all its forms to maximize the value of pharmaceutical spending.

These issues are of important to the intrinsic quality of pharmaceuticals, the quality of prescribing and the proper use of medicines. Some strategies have been introduced over decades, and their influence is complementary to that of measures designed primarily to have economic effects in this field. For example, the mid- and long-term impacts of utilization review and education strategies on pharmaceutical expenditures require policy action at the national or organization level. These quality-driven approaches aim to lower the cost of certain chronic conditions through reduced additional health services costs and better choices of drugs. Under these programs, such as evidence-based practice guidelines and disease management, individuals would be identified as having a particular disease or health condition and as potentially high users of health care.

Education-related approach, academic detailing (also called outreach visiting or educational visiting) is a method of service-oriented outreach education for physicians. It provides an accurate, up-to-date synthesis of relevant drug information in a balanced format. Academic detailing was initiated in the U.S. and has been utilized in Australia, Canada, the U.K., and the Netherlands to assist physicians in making optimal prescribing decisions.13 The success of all of these approaches will be highly related with incentives in the design of payment schemes to gain the acceptance and cooperation of health professionals in hospitals or clinics.

The pay for performance (P4P) design is another strategy aimed at increasing hospital care quality and controlling the health care cost rising. The program encourages hospitals to offer high quality care by giving financial incentives- the hospitals provided higher quality care get more pays. There is limited long-term experience and evidence to support the efficiency of this strategy, same as the BNHI's initiatives on breast cancer, cervical cancer, asthma, diabetes, and tuberculosis care in 2000.

To date, the most powerful driver of long-term pharmaceutical expenditure growth, advancements in new medical technology, was not even mentioned in the strategy. Much doubt arises of the extent to which they can truly contain costs. Hsieh et al. compared the impacts of treatment expansion, treatment substitution and pricing on the growth of pharmaceutical expenditure during 1997 to 2001 in Taiwan.14 The analysis suggested that the introduction of new drugs leading to expansion of treatment, expansion and substitution of new drugs for existing drugs were the drivers of increased spending.14 Efforts have been made to ensure that new drugs added to the formulary listing process represent acceptable“value for money”for the payers. Many countries have established an independent expert review agency responsible for the health technology assessment (HTA).15 In this approach, HTA would provide effectiveness-value based evidence to support reimbursement and pricing approval decisions for pharmaceutical products.

This paper with compact and practical review of the various approaches which have been developed in different environment and tested to date in an effort to contain costs in pharmaceutical care. Some cost-containment strategies for pharmaceutical spending with the limited literature available on the effectiveness of, and their ability to alter future healthcare cost trends remain unclear. New approaches with a limited support or lesser degree of success have continued to emerge and are bound to expand further. It is important to know that the situation in western developed countries differs substantially from that elsewhere. Although the nature of the cost containment problem may be the same, it is not easy to adopt many of the solutions developed in other countries. Furthermore, the problem of cost containment for pharmaceuticals cannot be viewed separately from such issues as equity, market structure or the quality of therapeutic care. Whether increasing spending on high quality of care relies on the society's expectations on the value of health system regarding attainable and desirable health, whether these comprise disease prevention, curative services or the provision of care for the aged population, all put increasing pressure on the budget available for the NHI program.

This article was not written with support from or discussion with any pharmaceutical manufacturer.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Ru-Liang Shih, Manager, Claims Review and Drug Benefit Unit in the Bureau of National Health Insurance for having her precious comments on current price and regulatory policies in the NHI program for controlling pharmaceutical expenditure.

References:

1. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Cost Containment Strategies for Prescription Drugs: Assessing The Evidence In The Literature. March 2005. (Accessed Oct. 2009, at http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/7295.cfm )

2. Lee Y, Yang M, Huang Y, et al: Impacts of Cost Containment Strategies on Pharmaceutical Expenditures of the National Health Insurance in Taiwan, 1996–2003. Pharmacoeconomics 2006;24(9):891-902.

3. Crowley, Jeffrey S.; Deb Ashner; and Linda Elam, Medicaid Outpatient Prescription Drug Benefits: Findings from a National Survey, 2003, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2003 2003. (Accessed Oct. 2009, at http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/Medicaid-Outpatient-Prescription-Drug-Benefits-Findings-from-a-National-Survey-2003.pdf.)

4. Bureau of National Health Insurance. National Health Insurance in Taiwan 2009. Outcome and Achievements:Improving Medical Care Quality. 2009. (Accessed Oct. 2009, at http://www.nhi.gov.tw/webdata/webdata.asp?menu=1&menu_id=&webdata_ID=2639&IsPrint=1.)

5. Fulda TR, Lyles A, Pugh MC, et al. Current Status of Prospective Drug Utilization Review. J Manag Care Pharm 2004;10(5):433-41.

6. Haas JS, Phillips KA, Gerstenberger EP, et al: Potential Savings from Substituting Generic Drugs for Brand-Name Drugs: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 1997–2000. Ann Intern Med 2005;142: 891-7.

7. Cheng T-M. Taiwan's New National Health Insurance Program: Genesis And Experience So Far. Health Affairs 2003;22(3):61-76.

8. Bureau of National Health Insurance. DRGs Payment System. 12/07/2009 (Accessed Dec. 2009, at http://www.nhi.gov.tw/webdata/webdata.asp?menu=1&menu_id=26&webdata_id=937.)

9. Bureau of National Health Insurance. Improving the quality of pharmaceutical products.10/01/2009. (in Chinese). (Accessed Dec. 2009, at http://www.nhi.gov.tw/webdata/webdata.asp?menu=3&menu_id=56&webdata_id=1138&WD_ID=.)

10. Witt D, Tillman D, Evans C. Evaluation of the clinical: and economic impact of a brand name-to-generic warfarin sodium conversion program. Pharmacotherapy 2003; 23: 360-8.

11. Kesselheim A, Misono A, Lee J, et al. Clinical Equivalence of Generic and Brand-Name Drugs Used in Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis JAMA 2008; 300(21): 2514-26.

12. Andermann F, Duh M, Gosselin A, et al. Compulsory generic switching of antiepileptic drugs: high switchback rates to branded compounds compared with other drug classes. . Epilepsia 2007; 48: 464-9.

13. May F. Academic Detailing Services: a proven strategy for clinical: practice improvement In: The 4th Asian Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology 2009 October 23-25; Tainan, Taiwan; 2009.

14. Hsieh C-R, Sloan FA. Adoption of Pharmaceutical Innovation and the Growth of Drug Expenditure in Taiwan: Is It Cost Effective? Value in Health 2008; 11(2): 334-44.

15. ISPOR Global Health Care Systems Road Map (Accessed Oct. 2009, at http://www.ispor.org/htaroadmaps/default.asp.)

摘要

藥物費用支出一直成長得比其他醫療項目支出來得快,已造成政府及醫療系統中相關人士相當負荷及憂心。台灣在全民健康保險制度下,藥物費用支出從1997年64億新台幣已增加到 2008年125.1億新台幣,且每年一直占總醫療支出大約25%。面對不斷成長的費用壓力,其策略不外是補足財務上不足或是限制該項費用支出;亦或是二者同步進行才能有效控制費用成長。由於挪用其他公共支出、增加健康保險費率或增加病患部分負擔各有其不同層次的困難度,通常各種能控制費用支出的作法或策略較易被廣為引用。

本文呈現文獻上提及幾項常被引用來控制費用支出的作法、討論控制費用策略可能衍生的利與弊、並提出其他可能的作法不僅長期可以達到控制費用支出,並可增進每一筆藥費支出的價值。

作者

高雄長庚紀念醫院藥劑科藥師 許茜甯