Abstract

This article reviews the changing pharmacist supply and demand over the recent past decade. Since 1999, there has been a severe shortage of pharmacists in community pharmacy, the demand peaked in 2006. To resolve the manpower issue, the academy responded by establishing new pharmacy schools and expanding existing programs to increase enrollment. In nine years (2000-2009), the number of graduates increased by 57%, of which 33% occurred in the last 5 years. The number of graduates in 2014 is projected to be over 13,000, in comparison with 7000 in 2001. The healthcare reform which will take full effect in 2014 and the baby boomer retirement wave may boost the demand for pharmacy services once again, as some have hoped. However, the general US economy and number of graduates may offset the market as a formidable neutralizing force. After 2009, reports of a declining pharmacy employment began to surface and the market continued to tighten in 2011. If not controlled, it is believed that the academy will begin to generate surplus of pharmacists in 2014. The article also touches on Taiwan's new PharmD -equivalent pharmacy program. It is hoped that the program will encompass quality and variety, and not to narrowly focus on clinical pharmacy. Unique features of traditional pharmacy education such as compounding, manufacturing and biotechnology are worth keeping. To transition the pharmacy practice to direct patient care model, not only pharmacist education is critical, education of the general public is equally important. Last but not the least, reimbursement issue regarding patient medication service must be resolved so that a smooth path can be paved for the next generation of pharmacists.

Key Words: Pharmacy Academy, Pharmacy Education, Pharmacy Graduates, Pharmacy Manpower, Supply and Demand, Employment Market

Introduction

There are many jobs that pay well and are still in high demand even in the midst of gloomy economy, according to the book“The 150 Best Recession Proof Jobs”by Laurence Shatkin 1. Of the top 10 recession proof jobs, six belong to healthcare professionals. Naturally pharmacy is one of them; the remainders are registered nurses, physical therapists, physicians and surgeons, dentists and dental hygienists, and medical and health service managers. Pharmacist is labeled as a recession proof profession for sensible reasons, among them less sensitive to economic downturn, higher pay scale, more current openings and projected workforce growth. It is also a great profession that truly offers equal pay and equal opportunity for men and women. In addition, it is one the few professions that afford work hour and work load flexibility for those who wish to succeed in their professional career while tending to their family.

Ten-year Employment Market Overview

In the recent past decade, there has been a grim shortage of pharmacists in community pharmacy. The imbalance of supply and demand began in 1999 and peaked in 2006. The recession that started the following December in 2007 virtually disturbed every segment of the US economy. Pharmaceutical sector is no exception, thankfully being affected to a lesser extent. Before 2009, pharmacy graduates appeared somewhat insulated from the declining economy despite increasing graduate numbers 2. During 2009 reports of a declining employment began to surface 3,4. In 2010 the job market continued to tighten 5. Severe economic down turn and high unemployment rate have caused many workers to lose their health insurance and fewer prescriptions were being filled at the pharmacy counter. According to IMS Health, growth of prescription drug sales slowed to a dismal 1.3% in 2008 compared with the previous year 3, and continued to slow in the following year 4. The results in some instances are less demand for pharmacist's service and fewer work hours. Graduates in areas hard hit by recession find it difficult to secure a full time position. This is an unpleasant contrast with the booming year of 2006, when employers were faced with the challenges of competitive recruiting. Sign-on bonuses and relocation benefits were commonly employed as incentives to effectively compete for graduates who typically received multiple offers. Employment challenges continued through 2010 and are likely to spill over to 2011. Pharmacy retailers stated that pharmacist openings were at the lowest level they had been in the past decade and that pharmacist salaries had stabilized or even somewhat receded. Staffing agencies for hospital pharmacists have observed some lay-off in a score of hospitals. In a recent job fair on our campus, I was told by a Wal-Mart district manager that there was only one full time vacancy for the whole Palm Beach County in south Florida.

The Aggregate Demand Index Trend

Knapp et al 6 published a comprehensive article that described the 10-year Aggregate Demand Index (ADI) trends from 1999 to 2010. ADI data were used to reflect “unmet demand” rather than ”demand” because the survey responses measured the extent to which the available supply of pharmacists met the demand of open positions. Therefore the ADI reflects both supply and demand conditions. The measures are based on a 5-point rating system where 5=high demand, difficult to fill open positions, 4=moderate demand, some difficulty filling open positions, 3=demand in balance with supply, 2=demand is less than the pharmacist supply available, 1=demand is much less than the pharmacist supply available. Three variables that would presumably influence the unmet demand for pharmacists were considered: US unemployment level, US pharmacy graduates and US retail prescription growth. ADI levels were at the highest in the early 2000s when the pharmacist shortage was severe 6,7. In January 2000, the national ADI averaged 4.33 and by January 2005 it had fallen off to 3.98. There was a rapid upswing in the ADI starting in the third quarter of 2005 that persisted for over a year. This time period coincided with the introduction of the Medicare Part D outpatient pharmacy benefits. The upswing peaked in August 2006 with ADI reaching 4.31. Since late 2006, ADI levels have been steadily falling. In February 2010, the national ADI fell to a level slightly above 3, suggesting a balance between supply and demand. The findings of this study established quantifiable relationships between ADI trend and US unemployment, US pharmacy graduates and US prescription growth rate.

Pharmacist Shortage or Surplus?

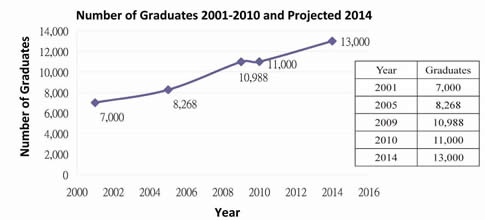

Or so the pharmacist shortage is over, thanks in large part to the increasing enrollment in pharmacy schools since 2000. Some pharmacy educators begin to raise the concern of a potential surplus of pharmacists 8. With addition of new schools and expansion of existing programs, the number of pharmacy graduates began to escalate, 7,000 in 2001, 8,268 in 2005, and 10,988 in 2009 and appeared to temporarily level off in 2010 at 11,000. This reflects a 57% increase in 9 years and 33% for the last 5 years alone. What is looming on the horizon is even more daunting. Three new schools will graduate a first class in 2011, nine in 2012, five in 2013 and six in 2014, notwithstanding the expansion of existing programs. It should be noted that rates of increase in the number of graduates reflect a 4-year lag period from the inception of pharmacy program. Based on a conservative estimate, the number of graduates in 2014 is projected to be over 13,000. (Figure 1.) shows the number of pharmacy graduates from 2001-2010 and the projected graduate number in 2014. Knapp et al 6 suggested that an increase of 20% in new graduates creates a relatively small impact on the overall work force based on the 268,000 pharmacists in the national workforce pool in 2010. However, over the long term, increase in graduates has a sustained impact because the larger cohort will remain in the workforce throughout their practice life. Delayed retirement can effectively increase the pharmacist supply, 3,200 full time equivalents 3,9 will be created with a mere 2 additional year retention.

The Favorable and the Unfavorable Conditions

Based on the current rate of US academy addition and expansion, it behooves us to ask the question, is the academic growth sustainable? Will the employment market shifts from a shortage to a surplus? Vivian 10 pointed to the prospect that by 2014 approximately 32 million uninsured Americans will gain access to healthcare benefits, including prescription drug through Medicare, Medicaid and other insurance. One favorable outcome of the healthcare reform will be a larger number of prescriptions generated, which would command more pharmacy services. In addition, new jobs are also likely to be created in response to the healthcare demand of the baby boomer, whose retirement wave got in full swing in 2011. All these factors, plus the general improvement in US economy could shift, once again the pharmacist supply and demand equilibrium. While the outlook is largely encouraging, the question is whether the growth of jobs can accommodate the increasing supplies. In successfully resolving a legitimate manpower shortage issue, the pendulum may have over swung. I believe the academy is poised to create a manpower surplus. Continued growth without control may jeopardize the pharmacist supply-demand equilibrium. The quality of pharmacy education will be impinged as well. Many schools are already concerned with a dilution of quality in student applicants. I have been serving on the Admission Committee since 2005 and I can attest to this concern in person. New pharmacy schools are frequently staffed by junior faculty members and administrative leaders, which is typical characteristics of excessive growth. It is true that any system will eventually correct itself and reach a new equilibrated state. There is also no doubt that the natural selection process will prevail and that the fittest program within the academy will remain strong. However, the cost and languish are unnecessary and can be avoided if there is a willingness to exercise some degree of self-control. Granted, institutions have the right to establish a pharmacy program as they see fit, but with rights come the responsibilities. It is prudent that the institutions pondering the addition or expansion of programs consider more than the current demand of student applicants filing through the application pipelines.

Taiwan's New Pharmacy Education Paradigm

Taiwan's pharmacy education has just leap-flogged into a new era, with the admission of its first PharmD equivalent class in 2010 at National Taiwan University. While I am excited about this new evolution of pharmacy education, I hope lessons can be learned from the US paradigm. I am weary if other schools follow suit and eagerly venture into the 6-year program. Quality of program must be the first and foremost priority in our philosophy of education. And quality education must be supported by a soundly grounded infrastructure of faculties, administrators, facilities (experiential sites for example) and yes, students. As the US PharmD program quickly expanded in the 2000s, many pharmacy schools were affected by the dilution of quality applicants. Quality may also be compromised by the caliber of faculty members and administrative leaders. Some new programs are staffed with a majority of junior faculties who are either fresh graduates themselves or with very limited academic experience. I am not suggesting age before beauty, but even the accreditation body would prefer a balanced mix of faculties with different levels of seniority, expertise and experience. Arguably true, many of the 70% graduates who file into community practice feel under-utilized because most chain pharmacies are still dispensing oriented. Direct patient care is an ideal not necessarily embraced by the store manager or the corporation. The dismantling of consultation booth at Walgreen stores serves as a gleam reality. The business model will continues to evolve and the outlook is hard to predict. We know the education system is ready and the students are ready. But is the patient fully prepared and is the business model conducive? On the other spectrum of practice, graduates with ambition to practice clinical pharmacy in the hospital setting, to my opinion are under-trained because of the limited experiential facilities and diluted curricula. They typically need to pursue a residency or fellowship training to become competent practitioners to work side by side with their peer healthcare providers.

The Horizon and the Outlook

With robotic pharmacy looming in the horizon, I will be surprised if the demand for dispensing pharmacists will not diminish in the hospital setting. That will cause the migration of more pharmacists into the retail setting at the community level. The bright side of this development is that pharmacists now will have unique opportunities to serve patients at the community level, particularly in the supermarket setting. But again the business model will dictate the fate and extent of such patient-oriented practice. Some are hopeful that medication therapy management (MTM) will provide value-added service to the patient. The question is who is going to pay for the added value and service. In the US, MTM service was off to a slow start in sporadic pharmacies and is still progressing at a crawling speed. The third party insurance reimbursement is a handicapping issue; the service model will not prevail unless the payment issue is resolved. A pharmaceutical care service equivalent to MTM is also offered in the Japanese pharmacy, and to my knowledge it is not moving with any great momentum. The reason is probably more cultural and less related to the reimbursement bureaucracy. Fortunately, the solution to payment issues may come easier in Taiwan because of our national insurance system. If we are able to successfully legislate the pharmaceutical care service within the overall reimbursement framework, we will be off to a smoother path than our US counterparts who are still struggling with the private insurance providers. In a downturn economy, it is tough to market a legitimate service even we know it's better for the patient and for the healthcare system as a whole in the long run.

The Vision and the Hope

Pharmacy practice is still morphing, as many other professions are as a matter of necessity, and the education program evolves along in attempt to lead the profession. To share the insurance budget pie, it's important for pharmacists to be proactive in participation in the political and social-economical environ of the healthcare system. We must present ourselves as team players but not competitors, working in conjunction with other healthcare providers for the welfare of the patients and the society as a whole. Moreover, pharmacy profession should be more than direct patient care. There are unique opportunities in compounding, manufacturing, biomedical engineering and biotechnology innovation. The ideal pharmacy curriculum should be one with diversification, not concentration, much like a balanced investment portfolio. The US PharmD program has been overly tilted toward clinical pharmacy at the expense of other subspecialties, and the outcome is by no means satisfactory. This is a great lesson for us, free. But first and foremost, let's pursue a controlled growth. Just imagine if we generate 500 PharmD a year from the established pharmacy programs in Taiwan, where are we to place them? Hospitals won't be able to accommodate the inflow of the produced manpower. Without a major shift in the job market paradigm, most pharmacists will still practice more or less traditionally, feeling under-utilized, frustrated or even over-invested.

References

1. Shatkin, L. The 150 Best Recession Proof Jobs. JIST Publishing, November, 2008.

2. Payer M. Pharmacist labeled a“recession proof”job WTOC 11. March 10, 2009 http://www.wtoc.com/global/story.asp?s=9981170. Assessed March 12, 2011

3. Veiders C. Recession Pool of Available Pharmacists. Supermarket News. June 8, 2009.

4. Recession Presents Challenges for Pharmacists. Drug Topics. June 12, 2009 http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/associations/recession-presents-challenges-for-pharmacists/articlestandrad/article/detail/603267. Assessed March 12, 2011

5. Trang DD. Is the pharmacist shortage over? Drug Topics. January15, 2010 http://drugtopic/modernmedicine.com/drugtopics/modern+medicine+now/pharmacist-shortage-is-it -over/article/articlestandard/article/detail/651922. Accessed Mar 12, 2011

6. Knapp KK, Shah, BM, Barnett, MJ. The Pharmacist Aggregate Demand Index to Explain Changing Pharmacist Demand Over a Ten-year Period. Am J Pharm Edu. December 17, 2010 http://www.ajpe.org/view.asp?art=aj7410189. Accessed March 12, 2011

7. Knapp, KK, Livesey JC. The Aggregate Demand Index: Measuring the Balance Between Supply and Demand. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002; 42 (3):391-398

8. Brown D. From shortage to surplus: The Hazards of Uncontrolled Academic Growth. December 15, 2010 http://ajpe.org/view.asp?art=7410185&pdf=yes

9. The Adequacy of Pharmacist Supply. Health Resources and Services Administration. Rockville, MD 2008

10. Vivian JC. HealthCare Reform Legislation: Part I. May 20, 2010 http://www.uspharmacist.com/content/d/pharmacy_law/c/20824/dnnprintmode/true/?skinsrc=[1]s

摘要

本文回顧美國就近十年來藥師供求關係的演變。藥師的缺乏從1999年開始到2006年達到高峰,為了解決藥師的缺乏,美國藥學教育界建新藥學院和增設分校來擴大招生,從2000到2009的九年之間藥學畢業生增加了57%。從2001年的7,000名畢業生到2014年預計將超過13,000人。事實上從2009年開始到現在,就業機會己經有明顯衰退,雖然有人設想醫療制度改革和嬰兒潮會增加藥師的需求,可是這些有利條件可能被經濟復甦的緩慢和畢業生增加的數目抵銷。假如藥學院校的增設不能有效控制,2014年以後可能有藥師增產過剩的隱憂。本文也約略提及台灣模仿美國的新型藥學教育,希望課程規劃能兼顧品質和科目,典型的葯學教育科目譬如調劑制劑和生物科技還是值得保存,即將邁入病人導向的執業模式,藥師教育重要,病人宣導也同等重要,對病人服務的保險給付要開始有解決的頭緒,為下一代藥師作舖路的工作。

作者

美國佛羅里達州西棕櫚灘,棕櫚灘大西洋大學藥學院教授 李慶三

Fig. 1